It CAN be done!

There’s a fire-breathing dragon in my garage.

Carl Sagan proposed this thought experiment in a chapter of his book, The Demon Haunted World. It goes like this:

I tell you a fire-breathing dragon lives in my garage. You are fascinated and skeptical. You ask to be shown. I bring you to my garage where I reveal…nothing. Oh, I forgot to tell you the dragon is invisible.

You have an idea. Let’s spread flour on the floor so we can see the dragon’s footprints. I inform you that won’t work – the dragon hovers over the ground.

You suggest an infrared sensor, to detect the heat of the fire. Actually, I say, the fire the dragon breathes is heatless.

How about some spray paint, to render the dragon visible? No, unfortunately, I counter, the dragon is incorporeal. Paint will not stick.

This continues. You suggest ways to prove the dragon’s existence and I give reasons the tests won’t work.

Depending on my relationship with you, you might be inclined to dismiss me, my dragon, and the whole idea as ludicrous – shake it off, forget the whole thing, and move on with your life.

Or, if you have a particular fondness for me, or simply have to interact with me regularly, you might feel inclined to engage with me further and try to understand. There would be one significant, burning question on your mind, something you are dying to ask me.

“Why do YOU believe it’s there?”

If you’re reading this article, chances are, you have experienced the frustration and helplessness of talking to a friend or family member who holds conspiracy theory beliefs. There are reasons this act is particularly frustrating and often fruitless. There are reasons, very human and rational and normal reasons, people tend to want to believe in conspiracy theories, and there is a reason they are particularly challenging to address.

I want to be clear that I am not a psychologist, family counselor, or scholar on this subject. I simply have an interest and curiosity about conspiracy theories and the psychology behind them and have done a lot of reading on the subject. I have also had personal experiences with conspiracy theory-believing family members and tactics I have found to be helpful in navigating those waters. I provide links to information I have obtained elsewhere, and I try to be clear when I am expressing my own beliefs and ideas.

I have also written a post for this site that focuses on the psychology of conspiracy theory beliefs, which can be found HERE.

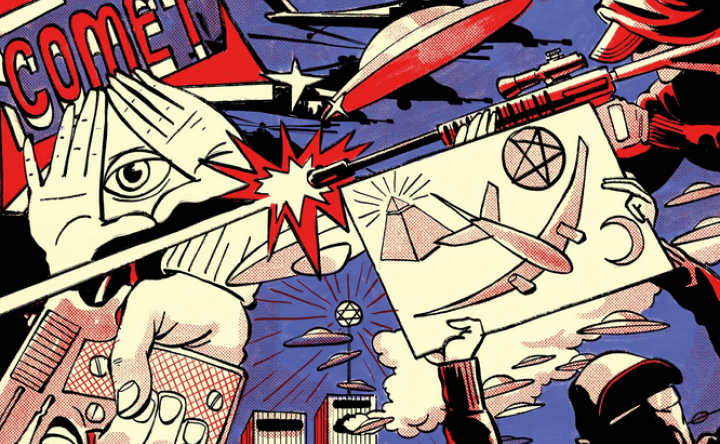

Conspiracy theory in this context applies to those conspiratorial beliefs that are unfalsifiable, meaning they are not capable of being proved false, like the dragon in the garage. Some beliefs are relatively harmless, like the Mandela Effect, but others can lead to radicalization and a very real physical danger for the believer and others.

At the very least, belief in conspiracy theories often leads to alienation and isolation. It is one thing when someone entertains an interesting suggestion of a conspiracy, but it is another thing altogether when they get sucked down a rabbit hole.

Here I have compiled a list of suggestions that I have obtained from literature, stories, blog posts, and my own experience to help improve your relationship with a conspiracy theory-believing friend or relative and to possibly plant some seeds of doubt in their theories.

A note about “planting seeds”: According to Bill Nye in a recent YouTube video, it takes approximately two years of exposure to evidence for a person to turn from a deeply held conspiracy theory belief. It’s a process that requires patience, support, and gentle nudging.

Judge the theory, not the theorist

The overall thesis of my article on conspiracy theory psychology is that belief in a conspiracy theory is consistent with how the human brain works. And therefore, my first bit of advice before talking to someone you value about their beliefs is to get off your high horse already!

Seriously, just because someone holds a belief that is irrational does not mean they are an irrational person. And furthermore, not all conspiracy theory belief is automatically irrational. Recognize that the difference between their view and yours likely boils down to a difference in how you each trust and evaluate sources of information. Not a difference in intellectual or critical-thinking ability.

Understand that this is your quest: To evaluate the merits of the theory and its supporting evidence, or at least their perception of those merits. It is not necessary or helpful to judge the person.

Remember this very important fact: Most human knowledge is collective.

Philip Fernbach gave a fun Ted Talk in 2017 called “Why do we believe things that aren’t true?” In it, he makes a startling statement. “As individuals, we do not know enough to justify almost anything we believe.”

You believe the Earth revolves around the sun. Can you explain the astronomical observations that allow you to believe this? You believe smoking is harmful to health. Can you explain the detrimental biological mechanisms that make this so?

The point is easy enough to make. You don’t necessarily understand the scientific, political, or cultural underpinnings of a concept, event, or discussion topic any more or less than your conspiracy-believing friend. Chances are, you are just more willing to accept mainstream consensus and official accounts.

Hey, me too. I believe in the power of specialization. I am grateful to those who have dedicated their lives to a field of study so I can benefit from their knowledge. So, if 95 out of 100 experts agree on something, I’m inclined to believe! Because I am willing to accept their assessments, not because I’m just so darn smart.

[I also believe in the power of generalization. Read my article on how Gen Z will be generalists!]

There is a phenomenon called the Debunker’s Fallacy. This describes the failure of a person to see connections even in the face of striking correlation, and an over-willingness to accept evidence as coincidence. While you are probably not exhibiting this, your conspiracy-believing friend is likely to see this in you. In fact, they almost certainly believe that you are woefully misinformed, that you have been horribly deceived, and they can’t understand why you don’t see the truth in front of you.

I am not saying you should be open-minded toward their worldview. I am simply suggesting you recognize the two-way street. The Golden Rule is at play here – treat them and their assessments as you hope they will treat you and yours.

Consider your goal investigation, not debunking, and certainly not shaming. Judge the theory on its merits, not the theorist on their beliefs.

Seek to understand their belief, not debunk or fact-check. Ask questions.

First and foremost, understand conspiracy theories are undebunkable by definition.

Consider Carl Sagan’s dragon example. There is no way to prove the dragon is there, but there is also no way to prove the dragon is NOT there. The natural question that arises is, “Why do you think there is a dragon here?” This is the mindset you should hold. The goal is not to convince your friend there is no dragon – it is to understand why they believe there is one.

This is best achieved through a series of questions. Start with, “What makes you believe this?” And go from there. Some questions I find helpful are:

“Why do you think they would do this?”

“What is gained by that?”

“What do you think will happen next?”

“Who are ‘they’?”

All of these questions help you to understand your friend’s beliefs, but they serve an additional purpose. They require the believer to evaluate their own understanding. Some conspiracy theorists will believe something wholeheartedly without realizing they aren’t clear on some of the most basic components.

When I speak to people who believe in conspiracy theories there is always a ‘they’. They want you to believe….or, they planned it from the very beginning…. The question I always ask immediately is, “Who are ‘they’? It is an important piece, for me, to understand the theory. It is also often answered with ambiguity. “The rich elite”, or “the Democrats,” or “the people behind the conspiracy.”

As you investigate their theory, they may be answering questions they hadn’t considered before. As you seek to understand, be sure you are filling in gaps of knowledge.

Conspiracy theorists will often overstate what their evidence proves. As an example, they may present evidence that the government, as part of the HAARP program, conducts atmospheric experiments in Alaska that affect the weather there. They may then claim this as proof that a series of midwestern tornadoes were intentionally caused by the Biden administration. Note the cognitive leap and ask to understand the connections.

As you seek to clarify, you are asking them to evaluate the merits of their own theory while remaining respectful of their beliefs.

Empathize

Note that, as mentioned in my other post, people tend toward conspiracy theories when they feel insecure, helpless, or powerless. They need answers and might be desperate to find them.

Inverse.com says the most powerful phrase when talking with a conspiracy theorist is, “I understand how you feel.” Be sympathetic to their need for a sense of control and understanding. They are likely wracked with distrust for the people in power and control. Conspiracy theories often suggest the powerful have even more power, and more control, than you can possibly imagine, and they are beyond nefarious to boot. Try to understand what that must feel like. Recall times you have felt powerless, misused, and mistreated; taken advantage of, lied about, distrusting, and victimized. Remember how that felt. Tell them you understand how they feel and mean it.

According to the New York Times, one of the worst things you can do is debate on social media. The space is unnuanced by personal interactions, like facial expressions, and you’re likely to get a performative response rather than an honest conversation.

Besides, in my own opinion, it’s disrespectful. They have chosen to share their views in their space. If they haven’t invited debate, you should share your opposing views in your own space.

The NYT also warns that some people see their beliefs as a significant part of their identity. Attacking the belief will feel like a personal attack no matter how you try to frame it.

Travis View, the host of the QAnon Anonymous Podcast, suggests showing conspiracy theorists the same compassion you would a friend in a destructive relationship. People engaged in conspiracy theories have often found friendship and community in these groups, and they’ve tied themselves and their beliefs strongly to these groups. It is not a simple matter to change their minds and walk away. Be empathetic of the complicated nature of these feelings.

Counter with your own beliefs on the subject

I have witnessed this tactic having an immediate disarming effect. Without comment on their belief; whether it is right or wrong, silly or faulty, or whatever you may think, simply state your contrasting belief on the topic.

This tactic is the opposite of seeking to understand and is more of an agree-to-disagree moment. The reply you give is probably not the reaction they expected or usually receive. As such, it may create a moment of reflection for that reason alone.

To apply this tactic, in response to a conspiratorial statement, simply state your opinion and its basis without comparison to theirs.

Them: “I believe the COVID-19 vaccine was engineered specifically to depopulate the Earth.”

You: “I believe it was designed to inoculate people so they will be better able to withstand infection.”

The statement is disarming in its reasonableness and de-escalating in its simplicity. You will not have changed their mind as they have not changed yours. You have agreed to disagree without disparaging their belief.

Here is another simple example.

Them: “I believe the US government is hiding aliens in Antarctica”

You: “I don’t believe our government is capable of pulling off a cover-up so complex.”

At worst, the opposing statement signals an impasse. At best, it may trigger a moment of thought on your statement. Remember that it takes many months or years of exposure to turn someone from conspiracy beliefs. Small pauses are big wins.

This tactic is critical because, as many other sources warn, you must take care of yourself. You must have a door you can walk through that releases you from the stress of a difficult encounter. If they wish to engage in further debate and you do not, apply the tactic again, shrug, and change the subject. Excuse yourself if you must.

Plant seeds, but carefully

If clarification is needed, to plant a seed in this context means to suggest an idea that you hope will stick in another person’s mind and grow. When dealing with the sensitivity that is necessary when suggesting someone you care about has a backward worldview, to “tread lightly” goes without saying.

You understand that your friend is engaged in conspiracy theories because they are distrustful and feel all too powerless. You will want to avoid becoming an enemy or just another somebody who cannot be trusted.

The trick with planting seeds is to make a casual statement that is completely true and that you believe. Don’t fancy yourself an actor, insincerity is not difficult to spot. The right type of statement is one they are unlikely to disagree with and yet will run counter to their logic.

If there is a chance you will come across as condescending or dismissive, consider holding off on making statements such as these.

Here are some suggestions –

Just casual:

“I’m an Occam’s Razor kind of person, the simplest explanation is probably true.”

“Sounds like the theory is unfalsifiable. I guess we may never know.”

In response to I do my own research:

“Me too, I definitely think we should be skeptical of official and alternative explanations.”

“I know how many years it takes to learn even just the basics in a field. Who am I to dispute the experts after some internet searching?”

Draw a parallel to something they know is false:

“It’s pretty normal to be skeptical of vaccines. Did you know that some people believed the smallpox vaccine would turn you into a cow?”

“Napoleon and Hitler were also thought to be the Antichrist, but I guess they weren’t.”

Have you had an experience you’d like to share? Add a comment. Love to hear from you.