In the late 1700s, an English doctor named Edward Jenner created the very first vaccine. The medical community suspected at that time that dairy farmers and milkmaids who were exposed to a relatively minor virus called Cowpox might be immune to the similar, but much more severe and deadly, virus Smallpox.

The accepted method of inoculation from smallpox at the time was to inject the patient with a controlled amount of smallpox and allow them to recover from the infection. It was risky and uncomfortable. Jenner believed that infecting the patient with a dose of cowpox might give the same immunity result with a milder reaction.

In a controversial experiment, Jenner injected a young boy with material from a pustule on the hand of a cowpox-infected milkmaid. After a time, he exposed the boy to smallpox and found the boy to be immune. His theory was confirmed.

Soon, this method of smallpox vaccination was commonplace, encouraged, and even sometimes required.

But not everyone trusted doctors, science, or the field of medicine, as you might expect. And in a fashion consistent with the human psyche, conspiracy theories arose. The rumors and fears were that, if you received this smallpox vaccine, you would turn into a cow.

Yes. That’s right. If you accepted this new-aged quackery of a vaccine, you just might sprout horns, begin to walk on all fours, lose the ability to utter coherent words, and develop an insatiable desire for an all-grass diet.

It seems silly now, but at the time, many people had heard of a friend of a friend of a cousin’s former roommate to whom this unfortunate fate had befallen. And it was terrifying.

I don’t tell this story to make fun. In hindsight, we can look down upon those who feared the march of science and the unknown because it is not unknown to us now. We can look back and reasonably believe that the smallpox-vaccinated remained bipedal people and did not become cows.

But we aren’t immune from the psychology that led people down the road of conspiratorial thinking. Not by a long shot.

What is a Conspiracy Theory?

Conventional word wisdom would lead one to conclude that a conspiracy theory is simply a theory about a conspiracy, where a conspiracy is any secret plot between two or more people. If I suspect that my neighbors are conspiring to drive me crazy with their windchimes, this would be a conspiracy theory. Once proven, it ceases to be a conspiracy theory and graduates into a full-fledged conspiracy.

But the common use of the term and its current application demand more specificity. The general, accepted definition of a conspiracy theory in psychology literature is a suspected plot carried out in secret, by powerful people, with a sinister goal. But this definition, too, is oversimplified, lacking characteristics defining the term.

A conspiracy theory nearly always involves distrust in the mainstream consensus of those with the qualifications to verify the accuracy of the conspiracy. For instance, the belief that historians are collectively concealing an aspect of history.

Real conspiracies are often uncovered due to ineptitude, leaks, and unexpected hiccups. A hallmark belief in a conspiracy theory, however, is the acceptance that the conspiracy has been perfectly planned and executed and that all elements and occurrences were deliberate and consequential. They often involve an inordinate number of contributors with no less than perfect secrecy amongst them.

Historically, conspiracy theories have always been prevalent, and they may be simply part of the human experience. Our brains are built in such a way to make conspiracy theories a part of our lives.

While it may seem that there are more conspiracy theories floating around than ever, evidence suggests this is not necessarily true. It can be argued, however, that they are more accessible and more spreadable now through the internet and social media. In other words, there may not be more conspiracy theories afloat than there used to be, but anyone looking for a theory, or for a community that believes in a theory, is readily able to find one.

The study of the psychology of conspiracy theories and conspiracy theorists is relatively new. Early investigations in the 1950s and ’60s focused on “paranoia” and took a historical approach — an after-the-fact type of review. In the 1990s, the study veered into cultural critiques, noting societal trends and historical episodes. The psychology of conspiracy theories and those who believe in them, on an individual level, didn’t take off until 2008.

Typically, research studies are conducted via surveys and interviews. Testers often ask participants a series of questions, and whether they agree or disagree with a list of statements. They compare those answers to other psychological factors to determine a profile.

Questions may be broad, like, “A lot of important information is deliberately concealed from the public out of self-interest,” or more specific, such as, “There was an official campaign by MI6 to assassinate Princess Diana, sanctioned by elements of the establishment.” The participants are asked to rank such questions on a scale of 1–5, from ‘definitely not true’ to ‘definitely true’.

Oftentimes, researchers will expose their subjects to an element — a story or some information, hypothetical or factual, designed to have a specific effect — and note the impact on the subject’s survey answers.

It has been found that engagement and belief in conspiracy theories are derived from three types of psychological motives: Epistemic, existential, and social.

Epistemic Motives

Belief in conspiracy theories can arise from a strong desire for knowledge and certainty. People tend to seek out explanations for events and circumstances. Often mainstream explanations aren’t satisfactory, and people may have a sense that information has been withheld.

This may very well be the case, for a variety of reasons. In some cases, the mainstream explanation may be lacking because complete information simply isn’t available. People need to have their questions answered and it is human nature to seek those answers. If they are not satisfied with official accounts, they may be willing to accept alternative explanations that seem to answer more of their questions.

Proportionality Bias

An arm of this motive extends toward a phenomenon known as proportionality bias. Essentially, the bias argues that a really substantial event should have a really substantial explanation. For example, a pandemic causing global death and chaos is much too traumatic and life-altering to have a natural cause. Its existence must be intentional and sinister.

It is this type of bias that explains why the assassination of JFK sparks numerous conspiracy theories with deep rabbit holes while the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan has been easily accepted as a lone gunman acting of his own accord. Because Ronald Reagan survived the attempt, the consequences to the country and the world were considerably smaller, allowing the explanation behind it to be equally “small”.

In a nutshell, it can feel as if an explanation is not acceptable because it isn’t “big” enough, or it may feel that all of the information is simply not there, there must be more to it. This bias may lead people to seek additional, or more satisfactory, explanations for events.

Existential Motives

People have an innate need to feel safe and secure. Some may gravitate toward a conspiracy theory because it gives them a sense that events of this world are not random or out of control but that they are controlled in some way or another, even if they are being controlled by powerful and sinister people with evil motives.

In 2021, a series of deadly tornadoes swept through the Midwest. In some circles, a conspiracy theory emerged that the government was wielding “weather weapons” against its citizens. Bizarrely, there is security in the belief that the government intentionally caused the weather phenomena with diabolical weaponry because that understanding means that these events can be stopped by the heroic efforts of good people. If the events are controlled, that control can be usurped, and people can be saved.

Ironically, while people delve into conspiracy theory research as a way to feel more in control and secure, their research often has the opposite effect, making them feel less secure and with less control, driving them even further into the conspiracy world.

Illusory Pattern Perception

An element of this motive of belief is a tendency to discover patterns where none exist. This is common in the human psyche — our brains are trained to seek out and uncover patterns. This is why you may see a face on Mars or a bunny rabbit shape in the clouds.

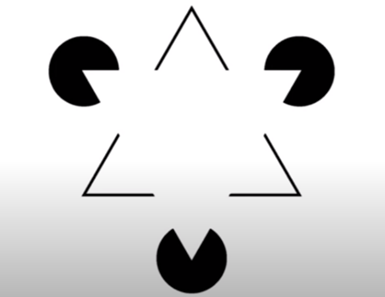

Take the above image. Your brain will distinguish two triangles and three dots, with one triangle lying on top. But look more closely. What is actually there are three “V” shapes and three Pacman shapes.

Researchers have found that people who have a greater tendency to discover patterns where there are none, say, in a Jackson Pollock painting, are also more likely to believe in conspiracy theories.

In one experiment, subjects were given the results of 100 random coin tosses with a sequence like, “HHHTTTTHH…”. Recognition of a pattern in the sequence was positively correlated with conspiracy theory belief.

Intent Bias

Another aspect of existential motives is a tendency to ascribe intention where none exists.

In a famous study from the 1940s, researchers presented subjects with an animation that showed shapes moving on a screen. The animation was designed to be viewed as though the shapes were behaving in certain ways — chasing, fighting, or helping each other. The study proved that human beings easily attributed motives to inanimate shapes.

More recently, the same animation was used in a psychological study on conspiracy theories. The participants of the study were shown the animation and asked questions about the consciousness and humanity of the objects on a scale. Those test subjects who reported the shapes more highly on the consciousness scale were also more likely to believe in conspiracy theories.

The theory follows that people are likely to attribute intent where it isn’t there, and this leads them to believe there are sinister motives in seemingly innocuous actions or events.

A curious example is the name of the virus COVID-19. The CDC explains that this name comes from an abbreviated form of “coronavirus disease 2019”. But circulating social media posts claimed that the name was encoded with a secret and sinister message for those smart enough to discover it. The letter “C” translated to the word “see”, “OVID” was a variation on the Latin word for “sheep” (ovis), and the number “19” was an ancient military code for “surrender”. Voila, “See sheep surrender”.

People also may tend to attribute extraordinary intent to others. Conspiracy theorists tend to view conspirators as almost maniacally evil, or Evil incarnate. They are inhumanly cruel, committing unspeakable acts against the unsuspecting public for the sheer thrill of it.

The need for understanding, knowledge, and control leads to the third psychological motivation.

Social Motive

Human beings have a need to feel good about themselves and about the groups to which they belong. People who feel underappreciated, underutilized, and underestimated are more likely to believe in conspiracy theories.

There is an element of narcissism involved. People feel good, and of elevated status, when they know something others do not know. Their engagement in a conspiracy theory makes them special and unique as they are “in the know”. They are not sheep — they rise above the common understanding and official reports to find the elite knowledge. They may find themselves important and special enough to be persecuted for their beliefs which distinguishes them from the masses.

These elements apply to groups as well as individuals. Followers of QAnon meet with each other to share information and ideas to which only they are privy. They are in the special order, an exclusive club, and they connect strongly with each other over their shared, uncommon knowledge.

Projection Bias

Projection is a commonly applied concept in psychology. In conspiracy theory psychology, projection is used to thrust motive and intent onto suspected conspirators. Research has found that people are more likely to believe in a conspiracy theory if they believe that, given the opportunity, they themselves would participate in the conspiracy.

For example, researchers asked a group of subjects, if they were part of the royal family, would they have considered participating in a secret plot to assassinate Princess Diana. Those who responded affirmatively were more likely to believe that there was a plot to murder Diana. Those who said they would never consider such a thing were more likely to believe that the plot did not exist.

Intuitively, believing you may have participated in a sinister plot given the chance opens the door to believing someone, a someone who was actually given the opportunity, would certainly have done so.

The Hero’s Journey

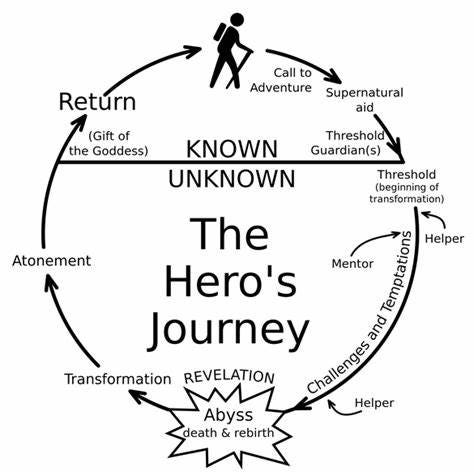

With these motives in mind, we can examine why certain conspiracies take hold and stick in the population. In a 2020 Ted Talk, Rachel Runnels gave a compelling argument. She believes conspiracy theories are especially successful when they invoke the narrative of The Hero’s Journey.

The Hero’s Journey is a narrative template that many popular hero stories follow. In the hero’s journey, the hero receives a call to adventure, leaves the relative comfort of his commonplace life, comes upon a mentor who provides knowledge and guidance, faces challenges and temptations, finds what he is looking for, then returns a changed man. Think Odysseus, Luke Skywalker, Harry Potter, etc.

As Runnels explains, the Hero is coached by the Mentor, faces the Shadow, and emerges victorious and changed for the better. Many conspiracy theories and their organizations follow the same model, with the truth seeker (conspiracy theorist) cast in the role of Hero. The Flat Earth Society will help you face the Shadow, NASA, as the truth is revealed. Q will guide you on your quest against the satanic cabal of the elite.

The narrative template has a profound psychological impact on us because it is so familiar and relatable.

The Number One Factor

The biggest psychological risk factor that determines whether someone will adhere to and believe in a conspiracy theory is their belief in another conspiracy theory. Indeed, people who believe in one conspiracy theory are likely to believe in many.

In fact, those who tend to believe in conspiracy theories are also prone to believing in two or more theories that contradict each other. For example, one study showed that people who believed Osama bin Laden was killed long before he was reportedly killed by Navy SEALs were also likely to believe he is still alive. This phenomenon is explained by researchers as simply a willingness to entertain multiple potential conspiracy versions when the official explanation “seems fishy”.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, some research has found that people with a tendency to gravitate toward conspiracy theories are actually notoriously bad at ferreting out real conspiracies. In fact, no real conspiracy has ever been uncovered by a conspiracy theorist and instead are usually brought to light by journalists and whistleblowers.

One explanation for this is that conspiracy theorists are always thinking bigger. They view all conspiracies as ultimately connected to each other. Actual conspiracies, inevitably on a smaller scale, are considered inconsequential, serving only to prove the potential for larger conspiracies. So, a simple government wiretapping can fly completely under their radar unless it is connected to the larger conspiracy of a giant government satanic cabal of child sex traffickers.

You may also notice that many conspiracy theories include an element of connection to JFK, and a fondness for the phrase, “It’s all connected.”

It’s Human Psychology

Whether you are one with a tendency to believe in conspiracy theories or you attribute lunacy to those who do, it is valuable to recognize that this psychology of a conspiracy theorist is not abnormal, per se. It is supported by the psychological workings of the human brain.

Some have attributed these tendencies to evolution, explaining that a sense of distrust and paranoia have benefitted our species and kept us alive. This is called the Adaptive Conspiracism Hypothesis, asserting that humans have adapted to be alerted when others may be conspiring against them.

A common analogy is this: You see an object in the distance that you believe is a snake, so you go the long way around to avoid it. If it turns out to be only a stick, you have merely wasted time. But if you had thought, that is probably just a stick, I’ll walk right past it, and it turns out to have been a snake, the consequences are deadly. The genes of the one more likely to perceive evil intent, whether there or not, were more likely to propagate.

After all, there are real conspiracies. People, sometimes powerful and sinister people, engage in conspiracies and cover-ups frequently. Certainly, some conspiracy theories viewed as irrational will turn out to be true (like MK Ultra), while some conspiracies are discovered without ever becoming an outside-the-mainstream conspiracy theory (like Watergate).

I certainly don’t intend to suggest conspiracy theories are harmless. Besides the profoundly negative psychological impacts they can have on individuals, they can also be quite dangerous. Sometimes they have terrible consequences. But they cannot be eradicated without an understanding of the underlying psychology.

I have always enjoyed conspiracy theories as fun, clever, thought-provoking, and often hilarious suggestions. But I almost never, if ever, believe they are true. And the thought of someone believing in some of these ideas, and potentially acting on those beliefs, is frightening. It is particularly frightening because it seems so irrational, unpredictable, and unbelievable that someone could possibly adhere to such nonsense.

That is why the aforementioned research and findings are comforting for me. Just a small grasp of psychological understanding lessens my fear.

It is with knowledge and understanding that we can tackle the effects of conspiracy theories, both on people and on society.

With that in mind, check out this post:

Talk to a Friend About Their Conspiracy Theory Beliefs, Keep the Friend

We can learn to talk to each other and achieve great things as a society even when our own psychology so often gets in the way.

Because, oh, by the way, smallpox is the one and only human disease we have ever successfully eradicated. We did it by injecting everyone possible with cowpox.

And despite the decidedly human fear, distrust, and uncertainty, we didn’t turn into cows.